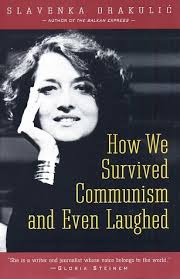

I found the following excerpts from the book How We Survived Communism & Even Laughed by Croatian author Slavenka Drakulić (1993) quite useful in explaining some contemporary situations in Macedonia, as well as providing general introduction for people from the Western block of the Cold War.

I have to add that as a citizen of Yugoslavia, a socialist country which was not a member of the Warsaw Pact, I grew with the notion that the Iron Curtain fell on our Eastern, and not on our Western borders. At the time we could travel almost anywhere in the world, thanks to Tito's balancing acts and feats of international diplomacy.

(pg. xvi-xvii)

I understand that in the West today ‘the end of communism’ has become a stock phrase, a truism, a common expression supposed to indicate the current state of things in Eastern Europe. It sounds marvelous when you hear it in political speeches or read it in the newspapers. The reality is that communism persists in the way people behave, in the looks on their faces, in the way they think. Despite the free elections and the celebration of the new democratic governments taking over in Prague, Budapest, and Bucharest, the truth is that the people still go home to small, crowded apartments, drive unreliable cars, worry about their sickly children, do boring jobs – if they are not unemployed – and eat poor quality food. Life has the same wearying immobility; it is something to be endured, not enjoyed. The end of communism is still remote because communism, more than a political ideology or a method of government, is a state of mind. Political power may change hands overnight, economic and social life may soon follow, but people’s personalities, shaped by the communist regimes they lived under, are slower to change. Their characters have so deeply incorporated a particular set of values, a way of thinking and of perceiving the world, that exorcising this way of being will take an unforeseeable length of time.

The following excerpt might explain why Macedonian newspapers frequently refer to leading politicians by their first names or nicknames, esp. in headlines. Somehow there’s no need to use the surnames – everybody knows who is Kiro, Branko, Ljubcho, Ljube, Johan or Grujo (pg. 16-17)

…Nobody seems to mind that there is no more food on the table – at least not as long as a passionate political discussion is going on. ‘This is our food,’ says Evelina. ‘We are used to swallowing politics with our meals. For breakfast you eat elections, a parliament discussion comes for lunch, and at dinner you laugh at the evening news or get mad at the lies that the Communist Party is trying to sell, in spite of everything.’ Perhaps these people can live almost without food – either because it’s too expensive or because there is nothing to buy, or both – without books and information,, but not without politics.The aspect of having no choice but to live at home has advantages as social net at times of dire poverty and abject unemployment, but its effects on individual growth must be taken into account (pg. 88-90, bolds are mine)

One might think that this is happening only now, when they have the first real chance to change something. Not so. This intimacy with political issues was a part of everyday life whether on the level of hatred, or mistrust, or gossip, or just plain resignation during Todor Živkov’s communist government. In a totalitarian society, one has to relate to the power directly; there is no escape. Therefore, politics never becomes abstract. It remains a palpable, brutal force directing every aspect of our lives, from what we eat to how we live and where we work. Like a disease, a plague, an epidemic, it doesn’t spare anybody. Paradoxically, this is precisely how a totalitarian state produces its enemies: politicized citizens. The ‘velvet revolution’ is the product not only of high politics, but of the consciousness of ordinary citizens, infected by politics.

…in 1987, a serious sociological study was conducted at Split University. Professor Srdjan Vrcan was interested in a characteristic but illogical phenomenon: why, in spite of probably the highest unemployment rate in Europe and the fact that about 85 per cent of the unemployed were young, there is not any kind of social movement or protest against an economy that forces people to wait an average of three years for their first job. The results confirmed what was already suspected: the reason is the conservative role of the family in our communist society. A relationship that from outside looks like a romantic tendency toward strong family ties in our culture has its less romantic side. Young unemployed people live in their parents’ apartments; their parents feed them, dress them, even give them some pocket money. The family furnishes complete protection and, in fact, young people have no reason to protest. Besides, protesting wouldn’t lead anywhere. The gigantic government bureaucracy – a system that was built just to keep communists in power and that perceives every spontaneous movement (whether for peace, ecology, or simple demand for jobs) as a threat to their rule – would put an end to any protest very efficiently. They would be considered ‘hooligans’ and punished as such.The book is worth reading as general introduction, even though some generalizations must be taken with a grain of salt, as the differences between countries, even between republics (of Yugoslavia, or USSR) must be taken into account. Moreover, different generations within the same location had vastly diversified experiences of communism.

But the problem is that even when young people get jobs, they cannot get away from their parents and still need their support. In such a society – all over Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union – young people cannot move up into important positions. They remain at the very bottom, no matter how skilled. It might be called youth discrimination. Parents could be accused of infantilizing their children and prolonging the status quo, but at the same time they are keeping their children off the streets. How can parents divorce children – or children parents, for that matter? Later on it is, perhaps, too late; the grandchildren have come, and who but grandparents will take care of them? Who want to expose kids to ‘care’ in kindergarten, to frequent illnesses, to early-morning dragging out of bed? Once again, when the children get a job and an apartment, divorce becomes impossible. To understand at least a little of this complicated situation, one has to know that this is a geriatric society, in which political leaders over sixty are considered to be ‘still young,’ not to mention those long dead, embalmed so they can live forever in their apartments – absurd mausoleums built of marble.

At the beginning, people multiplied in apartments. But later on, a strange phenomenon took place: apartments themselves started to divide and multiply. Like living organisms, prehistoric animals, protozoa perhaps, they divided into two or three, becoming smaller and smaller. Afterwards, with the help of a little money, they eventually got bigger again…

No comments:

Post a Comment